In response to a recent media article on a heritage-listed sewer “setting off a storm with developers” the National Trust is prompted to set out the work of its Industrial Heritage Committee, established in 1968 and, in particular, the vital role played by sewerage infrastructure in the development of our modern cities.

It is surprising to hear that anyone would have concerns about the heritage-listing of sewerage systems, thinking them “bizarre” and it does indicate that some people have no real understanding of the nature and importance of this vital heritage infrastructure.

Industrial Heritage can be just as interesting and historically important as say, churches and houses. See – UNESCO Study on Industrial Heritage for the World Heritage List.

The National Trust’s Industrial Heritage Committee was established in 1968 and is comprised of engineers, archaeologists and historians. Over the past fifty years that Committee has produced an Industrial Sites List of thousands of items and places across New South Wales categorised as Agricultural (e.g. barns, dairies, wool stores, abattoirs, silos, butter factories, machinery etc).

The National Trust’s Industrial Heritage Committee was established in 1968 and is comprised of engineers, archaeologists and historians. Over the past fifty years that Committee has produced an Industrial Sites List of thousands of items and places across New South Wales categorised as Agricultural (e.g. barns, dairies, wool stores, abattoirs, silos, butter factories, machinery etc).

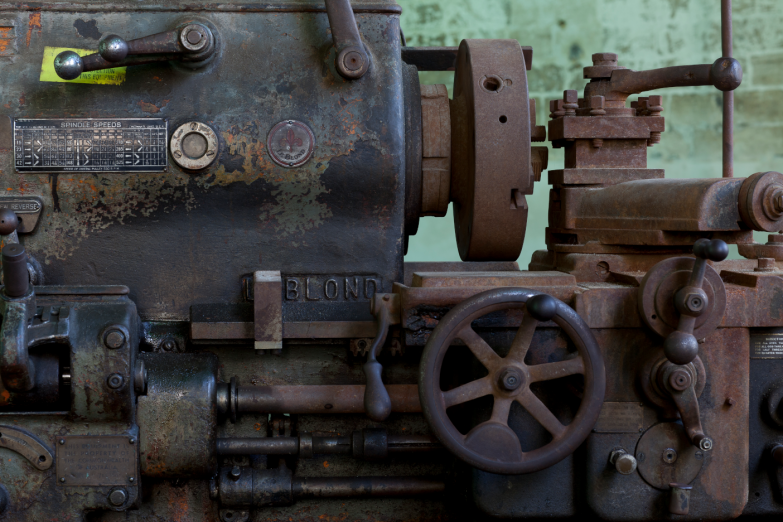

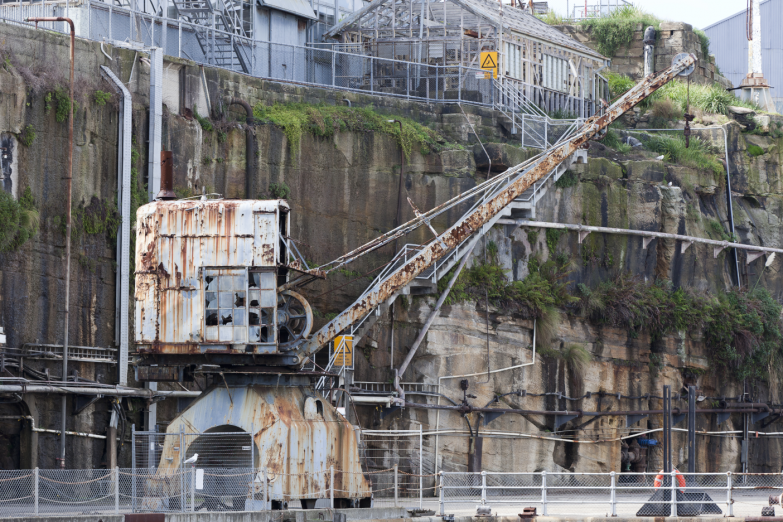

A large proportion of our heritage is, by its very nature, obsolete or heading in that direction – think blacksmith’s shops, wooden bridges, sawmill steam engines, railway steam engines (3801 & 3830), Cobb & Co roadside inns, paddle steamers, to name just a few.

The condition (state of disrepair) of an item should never be confused with its heritage significance. Heritage significance is based on a place’s history, cultural values, scientific values, aesthetic values etc. Once that significance is determined then the question of its condition (maintenance, conservation, restoration, re-creation) can be considered.

For example there are places of World Heritage Significance that are actually ruins – The Parthenon in Greece, Machu Picchu in Peru, Ancient Thebes in Egypt and after the fire, Notre Dame in Paris.

Then there are places of local heritage significance that are maintained in excellent condition by their owners.

Television shows such as Restoration Man and Grand Designs show how people are prepared to commit their lives and life savings to restore historic barns, churches and mills and re-adapt them for contemporary living.

If places or items are in such a state of disrepair or decay that their heritage values have been destroyed then they would not warrant heritage listing.

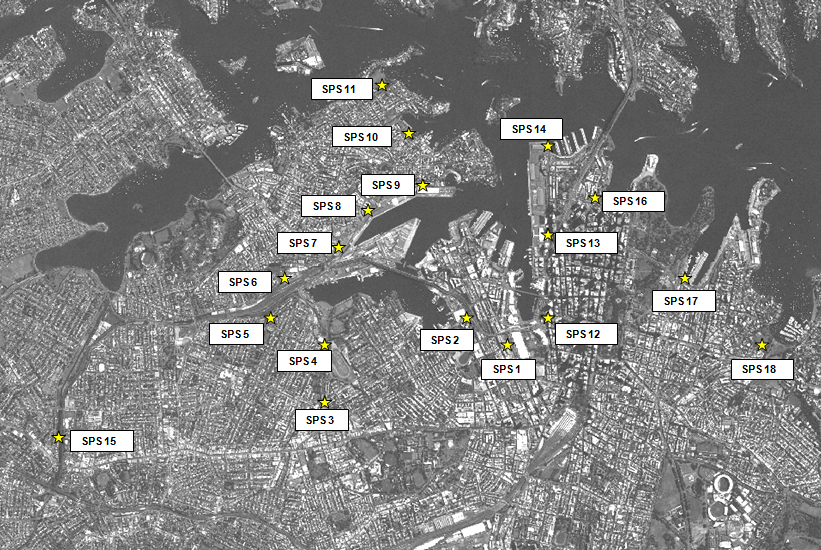

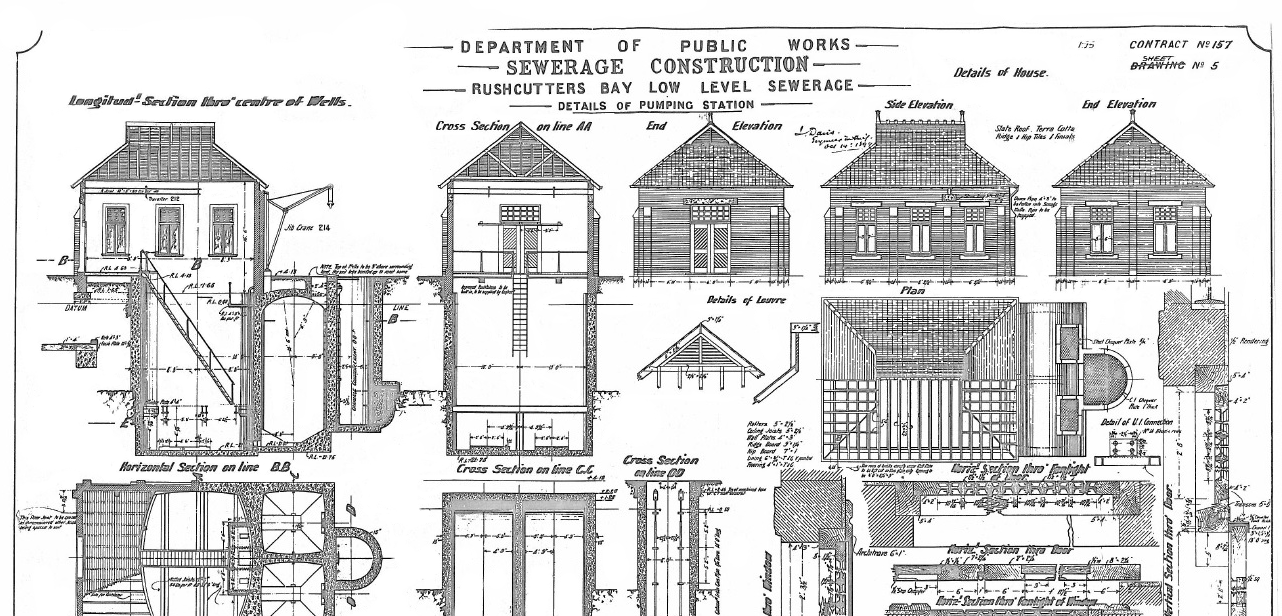

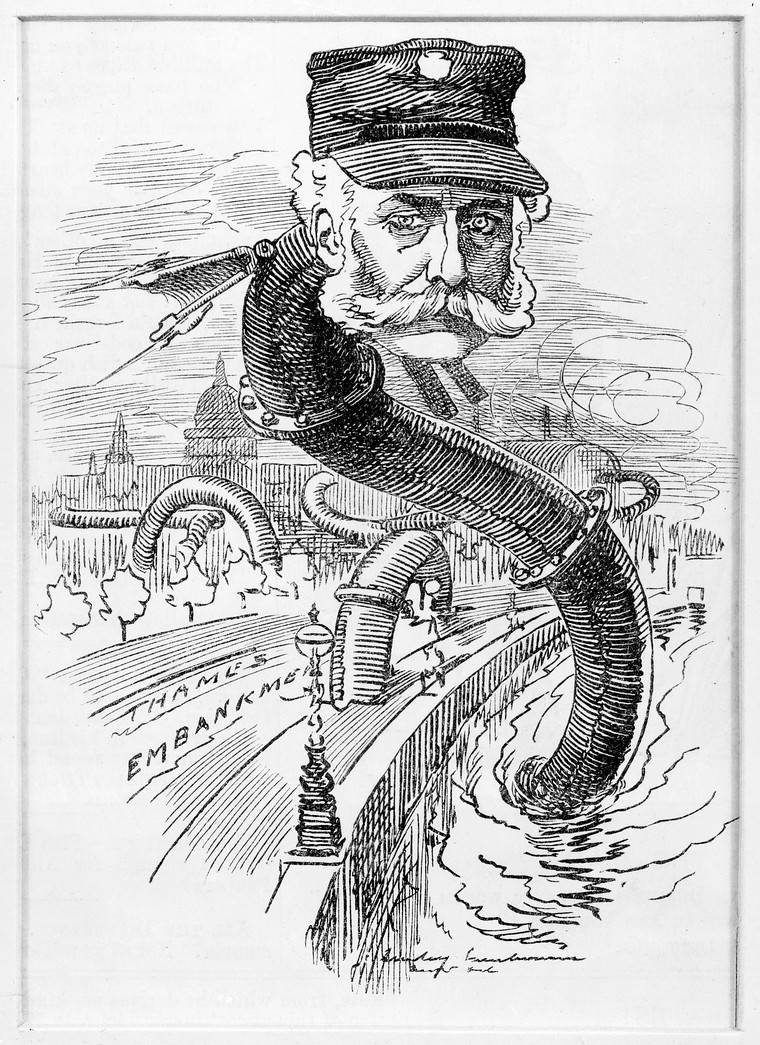

This same principle applies to Paris and its sewers and to Sydney. On the recommendation of its Industrial Heritage Committee, the Board of the National Trust approved the Listing on the National Trust Register of the Sydney Low Level Sewage Pumping Stations (LLSPS 1 – 18).

This same principle applies to Paris and its sewers and to Sydney. On the recommendation of its Industrial Heritage Committee, the Board of the National Trust approved the Listing on the National Trust Register of the Sydney Low Level Sewage Pumping Stations (LLSPS 1 – 18).